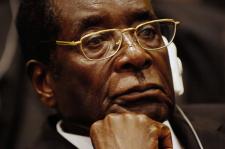

Mugabe’s Chaotic Reforms Enrich A Few And Impoverish Many

The epithet of “Uncle” is not always affectionate.

In Hollywood shorthand it’s sometimes used by younger women to cover a multitude of sins relating to older men.

In the mid-twentieth century it went as a prefix to the name of Josef Stalin, one of the greatest mass murderers of modern times.

And so it’s application to Robert Mugabe, the self-styled liberator of Zimbabwe, conjures distinctly mixed feelings, and not only amongst the white population of the country who he has so effectively disempowered and dispossessed.

Rumblings amongst the non-whites have a long history too, dating back at least to the Ndebele massacres, when Uncle Bob employed North Korean weaponry and know-how to commit mass-killings in the tribal heartlands of his main rival Joshua Nkomo.

These days though, Uncle Bob wields most of his power through economic leverage and patronage.

Zimbabweans are always aware that whenever there’s a currency or capital shortage the police and in particular the army always get paid first, while everyone goes without.

Not that not paying your officials is anything new in the annals of history – that’s something the European princes were doing constantly during the Thirty Years War, that the French were notoriously negligent about in the run up to the Revolution, and that even the Americans occasionally threaten when Congress talks of “shutting down government”.

In the case of the European princes, the French and the Americans though, they were not also simultaneously talking about the sequestration, along racial lines, of the assets of corporate entities.

Indeed, this ongoing facet of Zimbabwean politics is something more redolent of Nazi Germany’s racial persecution of the Jews than it is of any simple economic issue. If, that is, the policy was capable of being implemented with the efficiency which the Germans were, tragically, able to bring to bear.

But the Zimbabweans under Robert Mugabe have to date brought no such efficiency to bear for the simple reason that they can’t quite make up their minds what they want.

The straightforward thinking is clear enough. The Mugabe regime seeks some form of compensation for sufferings past - along the lines of those set up under the Black Empowerment regulations in the country’s neighbour South Africa.

The trouble is that the effectiveness of the South African system in actually redressing historical grievances is hotly disputed.

What seems to have happened instead in South Africa is that a powerful black oligarchy has managed to enrich itself while most of the rest of their compatriots remain entrenched in the situation they were in beforehand.

In other words, in economic terms, the end of apartheid has made no difference to the majority, and legislating assets into the hands of one ethnic group or another has had limited positive impact on the economy as a whole, although specific individuals have, to be sure, benefited greatly.

The idea that indigenisation in Zimbabwe will be handled more efficiently than it has been in South Africa is not taken seriously by any one.

Indeed, the chairman of the Economics Department of the University of Zimbabwe was recently quoted as saying that “the already privileged” are the ones likely to benefit from indigenisation.

“We saw this with the land reform programme.”

And indeed, looking back, it’s true to say that in the name of redressing historical wrongs, white farmers have been chased off land that had only been in their possession for a generation or two, to be replaced by itinerant and impoverished subsistence farmers with no know-how to bring to bear and no wider economic benefits to bring to the communities that they live in.

Whether this is a plus or a minus in the historical ledger is surely moot. The whites see the destruction of the country’s ability to operate in a modern 21st century economy. The blacks see an attempt at rebalancing hundred year old structural injustices.

The result: nobody wins. Or perhaps that’s a little unfair. For, as with Chu-Teh’s great quote about the French Revolution, it may actually be too early to tell.

The impacts of the European influence on Zimbabwe and the impact of the Mugabe-led counterattack are still being played out.

Some companies are doing CSR and a few individuals are getting seriously rich. But most people are getting poorer. A race to the bottom does equate to equality of a sort. But it’s a poor lookout for those who actually live there.

And that’s why talk of a Zimababwean diaspora is now commonplace and refers both to those with darker skin and those with lighter.